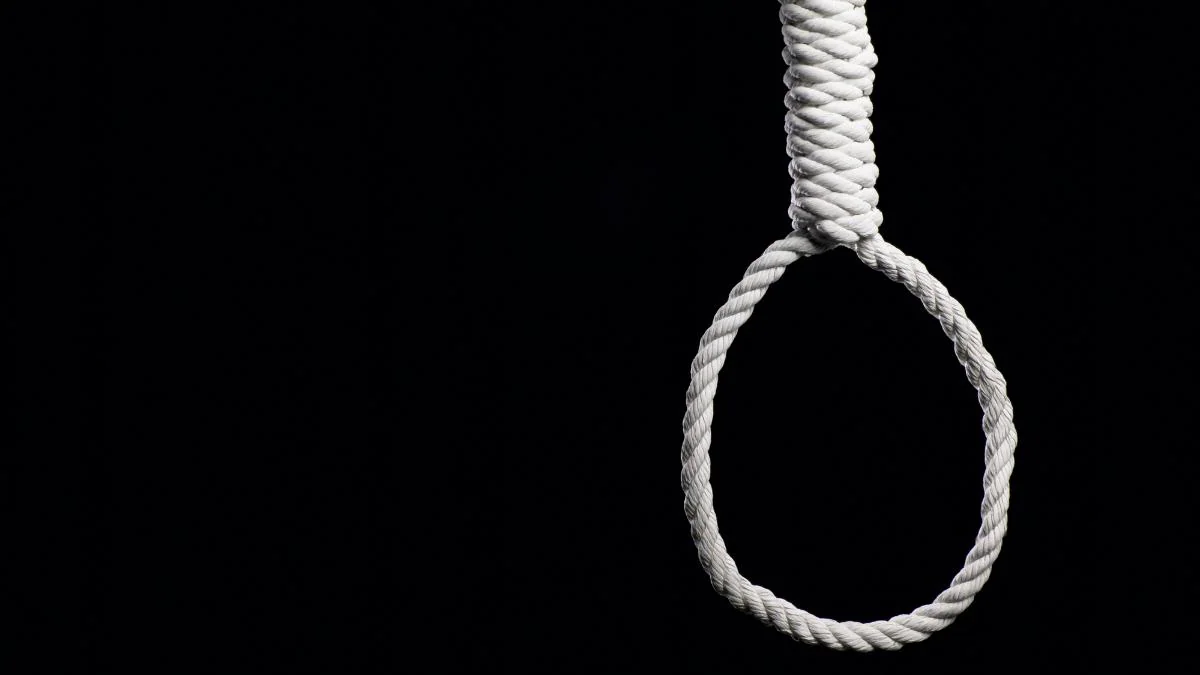

SC’s Caution on Death Penalty

Syllabus Areas:

GS II - Polity

In the first seven months of 2025, the Supreme Court (SC) heard 14 death sentence appeals and acquitted 7 entirely — the highest death sentence-to-acquittal ratio in recent years.

- The remaining 7 saw 4 commutations to life imprisonment and no confirmations of new death sentences.

- It has been over three years since SC confirmed a death sentence in a non-terror case (last was June 2022).

- This reveals a growing gap between trial courts awarding death sentences and higher courts overturning them.

Background:

- The constitutional validity of the death penalty in India was upheld by the Supreme Court in the landmark Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980)

- However, the Court limited its application to the “rarest of rare” cases, introducing safeguards that require judges to weigh aggravating and mitigating factors, consider the possibility of reform, and impose death only when life imprisonment is unquestionably foreclosed.

- All death sentences from trial courts are automatically referred to the High Court for confirmation.

- In Manoj v. State of Madhya Pradesh (2022), the Supreme Court issued a binding framework for sentencing in capital punishment cases, requiring trial courts to gather detailed information about the convict’s mental health, socio-economic background, family circumstances, and prison conduct, along with an assessment of the possibility of reform.

- This framework was intended to ensure a uniform and evidence-based approach to sentencing.

Key Points:

- The Supreme Court has not confirmed a single new death sentence in 2025, showing a clear pattern of restraint in capital punishment

- Between 2016 and 2025, High Courts were asked to confirm death sentences in 585 cases but completely acquitted the accused in 155 cases (25.5%) and commuted the sentence to life imprisonment in 313 cases (53.5%), resulting in an 80% rejection rate of trial court death penalties.

- The Supreme Court has emphasised that capital punishment should only be imposed with “unimpeachable evidence” and that the standard of proof must be applied with extreme strictness because human life is at stake.

- Judicial experts, including Justice Abhay Thipsay, have noted that trial courts are more likely to award death sentences because they hear cases soon after crimes, when public emotions are high, whereas appellate courts decide cases years later in a calmer environment.

- Data from Project 39A shows that trial courts awarded 1,180 death sentences between 2016 and 2024, but only 95 were confirmed by appellate courts.

- Despite the binding directions in the Manoj judgment, only four of the 139 death sentences handed down in 2024 complied with the required guidelines for evaluating mitigating factors and considering reform.

- There were 564 prisoners on death row in 2024 — the highest ever recorded in India — but the Supreme Court confirmed none of the death sentences it heard that year.

- Justice U.U. Lalit has pointed out that 75% of defendants in

criminal cases are below the poverty line, yet only 12% use free legal aid, often

selling their property to hire private lawyers.

- He stressed that legal aid in death penalty cases must be of much higher quality than currently provided.

Way Forward

- Strict Enforcement of Manoj Guidelines: Make compliance mandatory with legal consequences for violations.

- Sentencing Standardisation: Uniform sentencing framework across courts to avoid disparity.

- Better Legal Aid: Specialised, well-trained lawyers for capital punishment defence.

- Capacity Building for Trial Judges: Training on avoiding emotional bias, understanding mitigation, and upholding constitutional safeguards.

- Public Awareness: Educate society that capital punishment is exceptional, not the default.

- Data Transparency: Regular publication of death penalty trends and compliance rates.

The widening gap between trial court enthusiasm for death penalty and the Supreme Court’s cautious approach underscores the urgent need for systemic reforms. With the highest ever number of death row inmates in 2024, and overwhelming rates of acquittals/commutations on appeal, the Indian judicial system must address emotional bias in lower courts, ensure robust application of mitigating factors, and guarantee quality legal aid. The "rarest of rare" principle is not merely a moral ideal — it is a constitutional safeguard against irreversible miscarriages of justice.

Prelims Questions:

1. Which Article of the Indian Constitution empowers the President to grant pardon, reprieve, respite, or remission of punishment, including the death penalty?

- Article 20

- Article 21

- Article 72

- Article 142

2. The Supreme Court’s “rarest of rare” doctrine for awarding the death penalty was laid down in which of the following cases?

- Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980)

- Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978)

- Jagmohan Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh (1973)

- Mithu v. State of Punjab (1983)

3. The constitutional validity of the death penalty was first upheld by the Supreme Court in which case?

- Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978)

- Jagmohan Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh (1973)

- Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980)

- Mithu v. State of Punjab (1983)

4. The “procedure established by law” under Article 21 was interpreted to include fairness, justice, and reasonableness in which landmark case?

- Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973)

- Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978)

- Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980)

- Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration (1978)

Mains Question:

- "With higher courts overturning a majority of death sentences awarded by trial courts, examine the constitutional safeguards and judicial trends shaping capital punishment in India." (150 words) 10 marks